13/03/2025

Mapping Power in Our Social Movements

Does it ever feel like movement mapping is just a summing-up exercise? Something that creates an overview, but doesn’t tell you much about what’s going on or inform your next moves? If so, what might be missing is a deeper understanding of how power works within social movements.

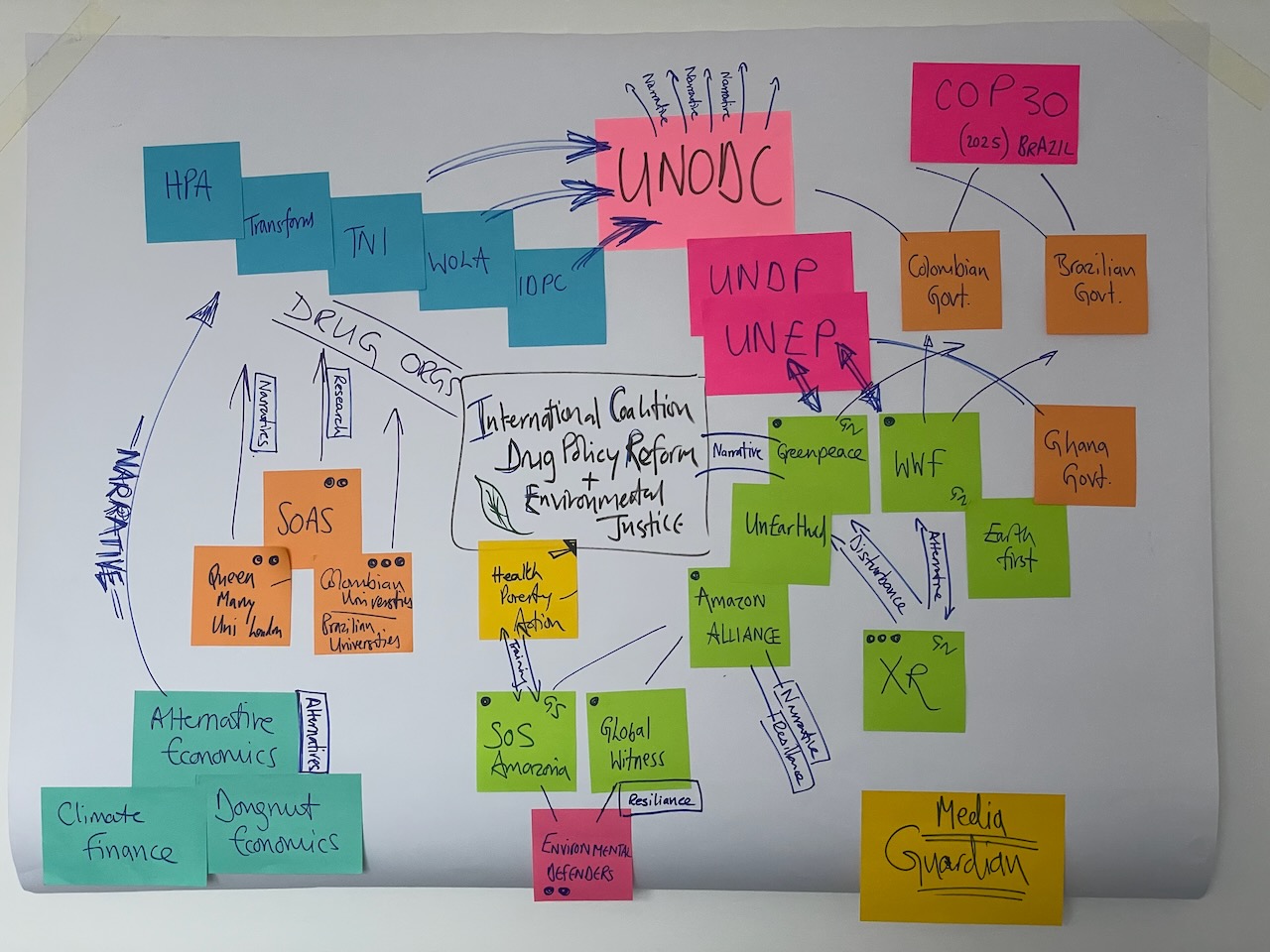

Movement mapping is often presented as ‘creating an overview of our movement’ – which is pretty accurate on a superficial level. We make an overview of all the actors that we interact with as an organisation in a movement, map out more actors in the movement, and then draw connections between them. We create a physical representation of the network of organisations and actors that make up a social movement.

However, to make it interesting and truly useful we need to dive deeper and scrutinise the influence and power groups and organisations have within our movements. How do we map power in movement mapping? More influential actors might get bigger sticky notes or cut-out circles in our workshops. But what constitutes the power that we attribute to them?

We like to think of ourselves as movement ecologists, and therefore we focus on connectedness. One way to find how power works in movements is by focussing on the nature of the relationships between actors. You can start by drawing an arrow from one actor to another, but then you ask questions like: Which resources flow between these actors? How do narratives spread between them? Who trains who? Which connections and dependencies are visible, which aren’t? What’s missing from the ecosystem, what niches remain unfilled?

Think about NGOs providing training or funding to grassroot organisations, nudging them towards certain activities and away from others. Or about how narratives are pushed by certain actors and become hegemonic within the movement. Sometimes bigger organisations within movements hold power in a social movement by being ‘thought leaders’ or define ‘proper’ theories of change or strategies. This can be helpful for a movement or limiting. In addition, new and disruptive actors might redefine the limits of what is possible by introducing creatively reconstructed tactics or strategies. If successful, older organisations have to relate to this new development and change or lose significance.

From such a detailed mapping, patterns emerge that can show us, e.g., where there is an abundance of resources in the movement and where there’s scarcity, how densely connected which parts of the movement are and in which way, and where there are ‘structural holes’ the closing of which would create social capital, innovation and strength.

Once we have a snapshot of the state of the ecosystem, we can start ‘gardening’. Gardening is not just about knowing which plant is which. It’s about knowing how the plants relate to the soil, the sun, fungi, animals and the rain, and how to optimise the relations in your garden. For movement gardening, it’s crucial to have a similarly detailed understanding of context and relations. Using this understanding, we can analyse what is needed and what we can do from our position. For example, certain narratives might need to be unpacked, changed or disposed of altogether. Maybe resource flows need to be altered to fully utilise potentials in the movement, maybe new connections need to be built and old ones reconfigured or cut.

If we understand power in our movements in this way, we can also increase the power of our movements.

Did you enjoy this post? Then share it with others! We are a small collective and depend on people like you to spread the word and get people to our courses.